|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Lex Maclean: [about a sick-looking portrait by Bacon]

It

looks just like our Bobby after a bad night out!

Gorbals: Ah'm sixteen

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

No Mean City

Yes -- I know the city like a lover.

Good or bad it's hard to love another that I've found,

This is no mean town, no mean city.

When I'm far away I long to see you.

In my mind I know you'll always be around,

This is no mean town, no mean city.

City life is strange,

you take your share of the good times

and the bad times.

Always something playing on your mind.

It's the only place that I would be willing to die for,

It's the only life I've ever seen.

Night or day she feeds me like a mother.

Good or bad it's hard to love another that I've found,

This is no mean town, no mean city.

Composed by Mike Moran.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

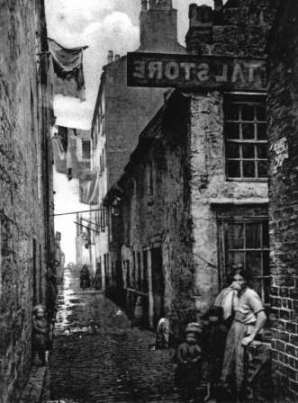

The Gorbals -

A community living on the razor’s edge

as violence rips it apart.

In a world where poverty slices deeper

than any flesh wound,

it takes more than a sewing machine

to make ends meet…

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

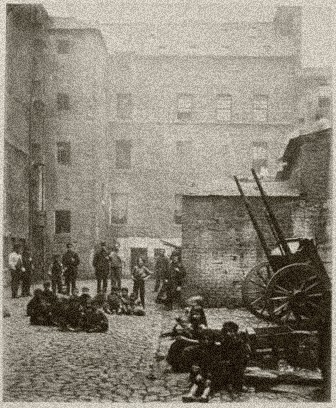

GORBALS 1948 –

A suppurating slum that

sprawls southward from the rat-ridden wharves of Scotland's Glasgow.

Most of the Gorbals' massive grey granite houses were built a century ago when thousands of poor laborers began to arrive

in Glasgow.

Now 85,000 human beings cram its 252 acres.

In many of its tenements 30 people share a single doorless

toilet,

and the odor of garbage hangs heavy in the stairwells.

There is an undertaker on every other block.

A Gorbals lad summed up life there:

"The cat sleeps with us.

If a rat runs over the blankets,

he springs out and has it."

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

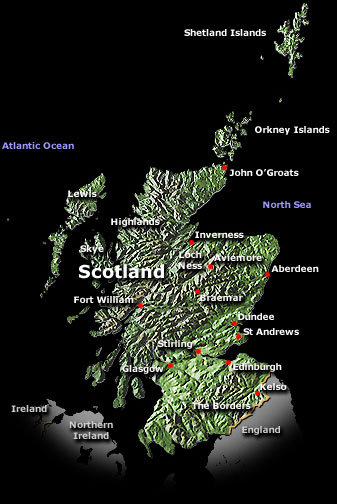

War, economic depression and social change characterized Glasgow

between 1914 and 1950. The outbreak of the First World War took most Glaswegians by surprise but there were signs prior to

this time that conflict was coming. In July 1914 King George V had visited the city during a high-profile tour of Scotland's industrial communities. Forming part of the itinerary

was Fairfield's shipyard in Govan, where he saw the super-Dreadnought

battleship, Valiant, under construction. That the Govan shipyard served as a showpiece for Glaswegian enterprise was

significant. Only two years previously, in 1912, the Burgh of Govan had been formally incorporated into the city's boundaries.

Along with other added areas, such as Cathcart, Partick and Pollokshaws, Govan had substantially boosted the number of Glasgow's inhabitants to over 1 million, making the extended city the most populous in the British Isles

after London.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

First World War

Less than a month after the royal visit, on 4 August

1914, Great

Britain and the Empire were at war with Germany. Tensions in the Balkans had undermined the fragile

balance of European power, with the result that alliances and counter-alliances were invoked to protect strategic interests.

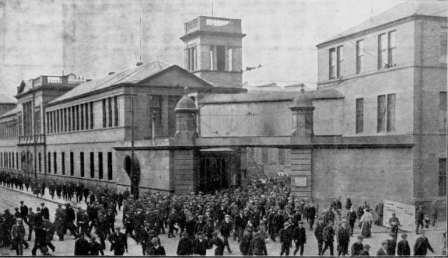

The fast pace of mobilisation immediately transformed Glasgow

into a major military recruitment centre, and the dual appeal of civic duty and defence of Empire engendered an enthusiastic

response from volunteers for active service. Over 200,000 Glasgow

men joined the armed forces between 1914 and 1918, either as volunteers, or, from January 1916, as conscripts.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

On the home front it was inevitable that

the productive capacity of Clydeside industry, especially shipbuilding, steel and engineering, should be directed overwhelmingly

towards the war effort. Glasgow became the centre of massive munitions output and the workforce

was placed under extraordinary pressure to ensure that the steady flow of armaments and military equipment was maintained.

During 1915 and 1916 the drive to boost manufacturing provoked industrial unrest. In particular, engineering trade unionists

viewed "dilution" of labour as a conscious attempt to deskill the workforce and thus reduce wage rates. Yet labour shortages

meant that women were increasingly recruited, especially for shell-making and the eventual female predominance in production

indicated how far conventional work patterns were temporarily reshaped by war.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Peace and Unrest

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 did not

herald an immediate return to peacetime conditions as the process of demobilisation was prolonged and elements of the war

economy still survived. Nevertheless, the wartime dislocation of global markets aroused fears of mass unemployment, a factor

that contributed to a brief resurgence of strike activity in January 1919. The city's inter-war reputation as the heart of

radical "Red Clydeside" was defined in the violent climax to a demonstration called by the engineers, when police and protesters

clashed outside the City Chambers in George Square. For the first time in fifty years the Riot Act

was read in Glasgow, the army was summoned to restore order

and strike leaders were arrested and imprisoned on incitement charges.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Coalition Government's alarmist reaction to the

events of "Bloody Friday" was based on the belief that there was a revolutionary dimension to the strike, an assumption that

was exaggerated but which nevertheless reflected the polarised political climate in Glasgow. From 1918 allegiances were starkly divided between

"socialist" and "anti-socialist" and although the labels masked a diversity of opinion, they came to dominate inter-war election

campaigns at both civic and parliamentary levels. Left-wing organisational strength had been consolidated during the war,

particularly within the Independent Labour Party. The ILP benefited from the 1918 franchise reforms which substantially extended

the electorate, even though women under thirty years of age could not vote for Westminster MPs until 1928.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Politics

Glasgow's political reorientation became apparent in the 1922 general election when Labour won ten out of

the fifteen parliamentary seats. Outspoken ILP-ers like James Maxton (1885-1946) and John Wheatley (1869-1930) ardently promoted

welfare issues at a time of bitter controversy over the city's deteriorating living standards. Labour also made significant

inroads at the municipal level, becoming the majority party on Glasgow Corporation for the first time in 1933. However, the

left was by no means politically dominant and Glasgow voters

still returned influential figures from the Conservatives and Unionists. For instance, Andrew Bonar Law (1858-1923) was Conservative

Prime Minister between 1922 and 1923.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

From the 1920s

the decline of Glasgow's once influential Liberal Party meant that politics became particularly fluid and

new parties emerged, such as the Communists and Scottish Nationalists, which attracted considerable minority support.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Depression

Glasgow's economy dominated political debate from the 1920s

as unpredictable international markets precipitated a downswing in the shipbuilding industry. This, in turn, affected other

key sectors such as steel. The world depression from 1929 cut across hopes of recovery as output collapsed and unemployment

levels soared. By 1931, in contrast with buoyant attitudes immediately before the war, one official civic publication was

decrying the negativity that undermined industrial confidence. However, motivational encouragement to proclaim Glasgow's "value and virtues" was not enough to halt the crisis. At the height of the depression,

in 1933, some 30 per cent of the city's insured population was out of work. By this time practical measures of regeneration

were identified as beyond local solutions, with state intervention and economic planning actively promoted to help investment

in new industries.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Social Problems

Inevitably the depression exacerbated social problems,

especially housing shortages and overcrowding. Certain communities experienced the disproportionate weight of congestion,

the most notorious being Hutchesontown and the Gorbals, to the south of the River Clyde. In 1931 almost 85,000 people inhabited

the area, which covered only 2 per cent of the city's total territory. It had long been a magnet for immigrants, particularly

from Ireland

and eastern Europe, and thus demonstrated an unusual cosmopolitan quality for Glasgow.

Yet sensationalist journalism embellished the "facts" of inter-war slum life and perpetuated an unsavoury image of the city

that survived for decades.

A favourite literary device was the metaphor

of infestation, whether by rats, street gangs, immigrants or socialists, to illustrate Glasgow's

crowded and corrosive slum environment.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Glasgow Story

1914-1950 - Irene Maver

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

We shall never

under any conditions submit to the

domination of the English.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

For so long as one hundred men remain alive,

It is not for glory or riches

or honours that we fight.

|

|

But only for liberty, which

no good man will consent to lose

but with his life.

THE DECLARATION

OF ARBROATH, 1320

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Courage of our Convictions

Whatever you do, you need courage. Whatever course you decide upon,

there is always someone to tell you that you are wrong.

To map out a course of action and follow it to an end

requires some of the same courage that a soldier needs.

Peace has its victories,

but it takes brave men and women to win them.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

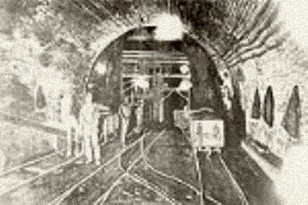

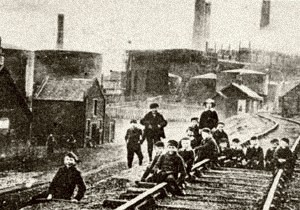

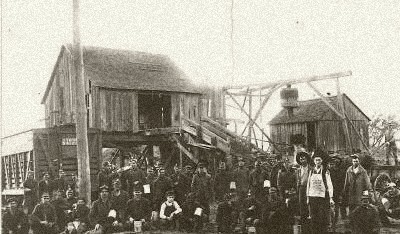

1921, 1926 Scottish Miners' strikes;

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Brief synopsis of events

Industrial relations in

the mining industry had long been fraught. Miners’ conditions improved

during the War and immediate post-war period when the mines were taken under government control and demand for coal was high

but an economic slump from 1920 and the return of the mines to private ownership (despite an apparent promise to retain public

control) created bitter industrial conflict. A national miners’ strike

in 1920 ended in compromise but strike action against wage cuts and local pay bargaining in 1921 failed and was marked, on

“Black Friday”, by the collapse of the Triple Alliance (of miners’,

transport workers’ and rail unions) and its promise of joint industrial action.

Wage cuts in 1925 were resisted by the threat of joint union action and averted by a nine-month government subsidy. The renewed threat of cuts in 1926, enforced by a miners’ lock-out, led to the

General Strike of May 1926, coordinated by the Trades Union Congress and involving some 1.8m workers. Government resolution trade unions’ lack of will or strategy to secure victory caused the strike

to be called off after nine days, having failed to secure conditions acceptable to the miners who held out.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Historical context

and analysis of impact

The coal industry

lay at the heart of the industrial revolution and by 1914 it employed 10 per cent of the British workforce. The industry’s fragmented, complex structure gave rise to troubled industrial relations and provided

ample grounds for confrontation between a management frequently perceived as obdurate and unsympathetic and a workforce with

a powerful sense of community and status. Further trade union militancy seemed

portended in 1914 in talks to create a Triple Alliance between mining, railway and transport unions but the First World War

intervened.

The War itself brought

improved pay, a national minimum wage, and government control of the mines. In

1919, the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) demanded a shorter working day, higher wages, and nationalization

of the mines. The Government temporised by establishing a Royal Commission under Justice Sankey, promising to observe its

recommendations. The Sankey Commission was divided but, in its final reports

published in June, a majority of commissioners (Sankey himself and the six labor representatives) favoured nationalization. However, the Government rejected public ownership.

In 1920, the MFGB resumed

its campaign for improved conditions but a brief national miners’ strike which broke out in October was ended inconclusively

by a temporary agreement matching pay rises to increased output. In 1921, the

economy fell into sharp downturn. The coal industry was particularly hard-hit

by the slump in demand and by the flood of German coal reaching the world market as part of the Versailles

reparations settlement. Britain’s

mines, hampered by inefficient organization and old-fashioned techniques, were badly placed to compete. The export price of

British coal fell by 50% and by 1921 the government was spending £5m a month to subsidize the industry. In February, it was announced that private control of the mines would resume on March 31. The mine owners announced drastic wage cuts and district agreements.

The MFGB’s refusal to accept these conditions led to the publication of lock-out notices to come into effect

on the day of de-control.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The miners’

union successfully called upon the aid of the Triple Alliance: transport and railway workers pledged to withdraw their labor

on Friday, 15, April. In truth, support for sympathetic strike action was lukewarm

and Alliance

leaders, most notably Jimmy Thomas of the railwaymen, were seeking an escape clause.

On the eve of the planned action, Frank Hodges (secretary of the MFGB) intimated to a meeting of MPs that the miners

might be willing to accept district settlements provided they were linked to the cost of living. Hodges was immediately repudiated by his executive but Alliance

leaders used the opening to accuse the miners of unreasonable intransigence and withdraw strike notices. The debacle became known, in labor movement mythology, as Black Friday.

The miners fought on for eleven weeks until forced to accept district settlements and wage cuts ranging between 10

and 40 per cent. Significantly, as many trade unionists had feared, the defeat

of the miners heralded a sweeping round of wage reductions that affected some 6m workers.

1921, therefore, played a crucial role in the origins of the much larger dispute that emerged in 1926. Industrial relations in the mining industry had been almost irreparably poisoned and some union leaders

concluded that it was only by effective concerted action that workers’ wages and conditions as a whole could be defended.

By 1925, 60% of British coal

was being raised at a loss and unemployment in the industry rose to nearly 18 per cent.

Mine owners announced that wages would be reduced by between 10 and 25 per cent on 31 July. The MFGB’s resistance concentrated on securing joint union action. Little came of the Industrial Alliance of manufacturing and transport unions which met in conference in

July 1925 but the TUC pledged full support to the miners at a meeting held on 10 July and the Transport and General Workers,

led by Ernie Bevin, and the National Union of Railwaymen promised to back the miners by an embargo on coal movements. The Special Committee of the TUC, created to coordinate the unions’ response

to the coal crisis, issued orders instructing members to embargo coal on 30 July. On

the same day, the Conservative Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin stated his belief in the general need for wage reductions. Support and sympathy for the miners combined with union members’ concerns for

their own living standards. On July 31, at the eleventh hour, the Government

announced the creation of a Royal Commission to investigate the mining industry (to be led by Sir Herbert Samuel) and a nine-month

subsidy to the mines pending its report. The climb-down was celebrated in the labor movement as Red

Friday.

This was a truce not a settlement. Whilst many in the labor movement celebrated, other cautionary and more militant voices

urged preparation for future conflict. The TUC created an Industrial Committee

to liaise with the miners and take charge of the dispute but meetings in October and December 1925 assumed no additional powers. The Government, on the other hand, acted decisively. In July 1925, the Supply and

Transport Committee was activated and ten Civil Commissioners were granted plenary powers under the 1920 Emergency Powers

Act to maintain transport, food and coal supplies, and postal services. In September

1925, the Organization for the Maintenance of Supplies (OMS) was established to supply volunteer labor in the event of any

general work stoppage. Though an unofficial body, it liaised

closely with government.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The report of the

Samuel Commission, when it came on 10 March 1926, disappointed all sides. It

opposed the labor movement’s nationalization scheme, though supporting state acquisition of mineral rights. It proposed rationalization of the industry and favoured improved welfare benefits for miners. But it was

adamant that government subsidy must be ended and that wage cuts were unavoidable. The

Government was shy even of the limited state intervention that had been suggested. Coal

owners opposed any infringement of their proprietorial prerogatives. Mineworkers

stood by their slogan, “Not a penny off the pay, not a second on the day”.

Four days later, the owners stated their intention to implement wage cuts and district settlements, and lock-out notices

were posted to take effect on 1 May.

The TUC’s Industrial

Council reiterated its full support for the miners but, significantly for later developments, was wary of fully backing the

MFGB’s refusal of any wage cuts, increased hours or district settlements. The

implication was that some reduction in wages might be acceptable provided the rest of the Samuel Report was fully implemented. The miners, nevertheless, placed the conduct of the dispute under the TUC’s

control. The TUC continued to negotiate for a settlement but Baldwin’s comment to the press that longer hours were necessary and news of the Government’s

preparations for a likely strike forced their hand. Last minute negotiations

between the Government and the TUC Industrial Council on 2 May were called off by Baldwin

when he heard of unofficial action by Daily Mail print workers in refusing to print an editorial hostile to the union

cause.

The TUC strategy was

to call out unions in two phases. Workers in transport, printing, building, metal

and chemical trades were to cease work from midnight, Monday 3 May. A second

phase, comprising engineering, shipbuilding and power workers, was to follow on 12 May.

The response was overwhelming; local organizers reported near unanimous support for the stoppage from the trades called

out and in many cases from workers not immediately affected. Nor were there

any but isolated signs of the strike weakening as the dispute progressed though these were a factor in the TUC’s decision

to halt the dispute. Most historians concur with the contemporary labour movement’s

claim that the strike demonstrated unprecedented class solidarity.

In total, some 1.8million

workers struck work over the course of the nine-day dispute.

Given the lack of

detailed preparation, the labor movement also fashioned an impressive apparatus to coordinate its action. Some 400-500 local organizing bodies were formed in which local trades councils frequently played a leading

role. These committees issued instructions, distributed permits for essential

services, and generally sought to maintain workers’ morale. A few more

militant committees established Workers’ Defence Corps.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Government, however,

acted forcefully to maintain essential services. The Civil Commissioners

implemented the plans already agreed and volunteer labor was recruited with the aid of the OMS. Meanwhile, Government propaganda painted the dispute as an attack on the Constitution, giving the pronouncements

of Sir John Simon MP and Mr Justice Astbury that the strike was illegal wide publicity.

Despite the aggressive rhetoric, relations between strikers and the forces of law and order were generally cordial

but the myth of a peaceful and “very British” conflict should be questioned in part. Troops were deployed to move

food supplies and clashes between pickets and police occurred in more militant areas.

The Government reported 1760 arrests during the strike.

Labour’s parliamentary

leadership, particularly Ramsay MacDonald, was equivocal in its support and the TUC itself was concerned to bring the dispute

to an early conclusion. Samuel was prevailed upon to act as an intermediary though

acting, as he acknowledged, with no governmental authority. The Samuel Memorandum

published on 11 May was essentially a rehash of his Commission’s previous report but the TUC seized on the Memorandum

as the basis of a settlement, ignoring the MFGB which, under the resolute leadership of its president Herbert Smith, maintained

its refusal to countenance wage cuts. On 12 May, a TUC deputation met Baldwin to announce that

the Strike had been called off. Baldwin, for

his part gave no assurances that the Samuel recommendations would be implemented.

The miners’ struggle

continued for a further seven months. The Government’s repeal of the Seven

Hours Act in July 1926 hardened feelings and union members continued to refuse terms that involved degraded conditions. But a break-away “non-political” union was formed in the East

Midlands and the hardships suffered by the mining communities impelled a slow drift back to work through October

and November. In these circumstances, the MFGB’s national conference

on 19 November agreed to allow its member associations to negotiate local agreements (in principle conforming to national

standards). The strike ended in abject failure with district settlements, longer hours, and wage cuts.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Impact

One immediate effect of the Strike was the passing

of the Trade Disputes and Trade Union Act of 1927. The Act declared sympathetic

and general strikes illegal, banned mass picketing and forbade government employees to join “political” trade

unions (those affiliated to the TUC or Labour Party). It also replaced “contracting-out”

of the unions’ political levy to the Labour Party by “contracting-in” - in other words, union members now

had to state expressly that they wished to pay the levy rather than the reverse.

Union contributions to the Labour Party fell by about one third, largely through the inertia of union members rather

than hostility to Labour as such. In fact, one of the effects of the Strike was

to increase working-class support for Labour. The class-determined character

of the General Strike and coal dispute and the apparently callous nature of Government policy heightened Labour’s appeal

as a specifically working-class party and after the1929 General Election it became the largest single party and formed its

second government.

Trade union membership fell,

particularly in those unions most closely involved in the dispute. Industrial

action declined significantly in 1927 and 1928 as a result of the depletion of union funds and a decline in members’

morale. But by 1929, union finances were largely restored and the number of strikes

increased. Generally, the union movement appeared to become more moderate. Its

left-wing rhetoric was toned down in the later twenties and the TUC made moves to reduce Communist influence in the unions. A more conciliatory industrial policy was symbolized in the Mond-Turner talks of 1928

- headed by the Liberal MP and industrialist Sir Alfred Mond and Ben Turner, the textile workers’ leader - though many

in the union movement as a whole had long favored cooperation with employers. The

mines were nationalized by Labour in 1946 but the economics of the coal industry remained difficult. A year-long strike against pit closures occurred in 1984-85 and a greatly reduced mining industry was privatized

in 1996.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|